Waste Not

The United States has an obsession with waste. Two Loyola alums are tackling it head on.

Maddie Sullivan (SES ’19) had no idea that a simple class assignment could define the course of her career.

In her final semester at Loyola University Chicago, Sullivan, an environmental science major, was knee-deep in post-graduation discernment, wondering how best to turn her passion for sustainability into a paycheck. In a course taught by Nancy Landrum, professor of sustainability management in the Quinlan School of Business and the School of Environmental Sustainability, Sullivan was assigned to interview Garry Cooper, CEO and co-founder of Rheaply, after he had spoken in their sustainability management course about his company’s work on the circular economy.

“I always tell my students to step up to the plate, talk to [guest speakers], ask about jobs, ask about internships,” Landrum says.

After completing the assignment, that’s exactly what Sullivan did.

Launched in 2016, Chicago-based Rheaply (whose name comes from the combination of “research” and “cheaply”) is an asset management platform that facilitates material and resource sharing—bringing to life one of the focal points of the circular economy: keeping products in use as long as possible. They work with research institutions, Fortune 500 companies, governments, school systems, nonprofits, and startups to assess what assets (computers, lab equipment, etc) they have that aren’t being used; these assets are then posted on their platform—picture something like Facebook Marketplace—where they can find a new home inside or outside of the organization.

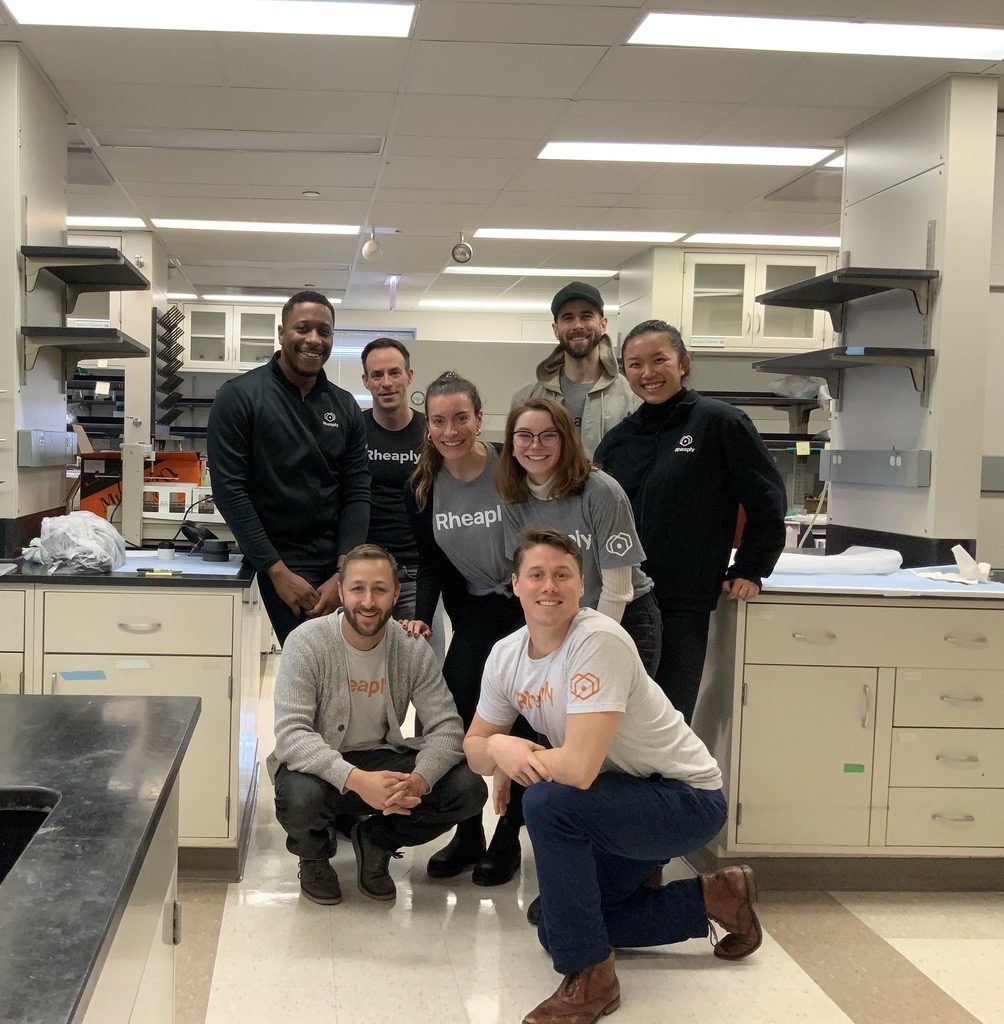

Sullivan was hired at Rheaply in 2019 as a customer success intern and rounded out their then eight person team. Since then, the circular economy focused tech start-up has grown exponentially, more than tripling their staff. And Sullivan has proved to be integral within the company, moving through four different positions in just two years.

“I’m really proud of Maddie for getting in on the ground floor and being part of that growth,” Landrum says. “To see your former students go into your line of business—sustainability—I get really excited about that.”

The whole goal [of the circular economy] is to teach businesses and economies how to operate more like nature so we can get rid of the whole waste thing we have an obsession with.

— Nancy Landrum , professor of sustainability management in the Quinlan School of Business and the School of Environmental Sustainability

While the circular economic model has made great strides in Europe because of sustainability-focused government regulations, such movement hasn’t been as widespread in the United States. Implementing circular economic practices would require a systemic shift across all fronts—businesses, government, and individuals. “The whole goal is to teach businesses and economies how to operate more like nature so we can get rid of the whole waste thing we have an obsession with,” Landrum says. Together we would have to fundamentally change the way we manage natural resources, create and consume products, and discard materials when we’re done with them. While ambitious, this type of economic model is not impossible.

“When you realize that the economy is designed, then of course you understand that it can be redesigned,” Chris Grantham, executive portfolio director and circular economy consultant at IDEO London, said at the 2018 Summit for the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF), the global leader in circular economy research and education. Rheaply is a member institution in EMF’s network, and Loyola is one of a handful of American universities that are EMF member schools, committing itself to pursuing research and education related to the circular economy. Initiatives such as the Searle Biodiesel Lab and the University’s aquaponics facility show how this commitment is alive and well on Loyola’s campuses today.

When Roma Patel (SES ’18) moved to Chicago from London, she didn’t expect how you dispose of plastic bottles to be a glaring cultural difference. While at a friend’s house, Patel was shocked to learn they did not recycle. “I was throwing something away and asked, where’s the recycling bin?” she remembers. “My friend said, ‘We don’t have one,’ and I thought, ‘What do you mean? How do you not have one?’”

That memory stands out to Patel as a sort of personal awakening to issues surrounding environmental sustainability in the United States. Another was a climate change course she took at Loyola, which inspired her to take on an additional major: environmental science. Another yet was the same sustainability management course taught by Landrum that Sullivan took.

“I think it was quite transformative for me to go through the courses at [SES],” she says. “They definitely led me to a place where I could explore more career options that pertain to sustainability and corporate social responsibility. I was very invigorated, very pumped up to have an impact on the world.”

Like Sullivan, Patel’s passion for sustainability and interest in the circular economy led her to Rheaply, where she was hired in 2021 on their product management team. The last year especially has helped Patel recognize the urgency in moving the economy toward a circular model. “Risks like a global pandemic, humanitarian crisis, extreme weather events, all of these things that we have to face will eventually catch up to us unless we change and design new systems that are resilient,” she says.

Sullivan agrees, noting that businesses have the biggest potential of making an actual difference in the world of sustainability today. “The future of sustainability is going to be in businesses, because they tend to be the leaders in trends,” she says. “Following and pushing businesses to be more sustainable is where you’re going to see a lot of movement in sustainability.”

Rheaply is one of these industry leaders that is making real strides in sustainability by illustrating the circular economy can work here in the United States. Since its founding, the start-up has helped companies divert more than 14.5 metric tons of waste through more than 5,000 transactions on its platform. That adds up to $1.6 million in cost savings for their clients.

And they’re not done yet. The company recently raised $8 million in funding to continue to scale their business.

“Almost every organization has this problem,” Sullivan says. “Physical items that are just sitting in storage closets or offices. We help bring visibility to these items so they can potentially be reused. Companies can get value out of their items until the very end of their life cycle.”

As sustainability continues to become more mainstream, hopefully the adoption of circular economic practices, and companies like Rheaply, will too. Rheaply’s CEO Garry Cooper, in a press release about the company’s recent funding, expresses his hope that peer organizations will “consider the stakes: either we develop and take to market additional inventive and practical climate tech solutions today, or future generations unnecessarily shoulder an impossible burden.”

Landrum believes government intervention, like what has been enacted across Europe, is the only way to move forward in a really widespread way in the U.S. “The key to change is legislation,” she says. “The E.U. has put all this in force at a federal level, and as a result, look at how far advanced they are.”

Sullivan hopes companies will realize how easy it actually is to implement circular practices into their businesses and how vital it is, and will continue to be, to have sustainability goals.

Sullivan agrees, noting that businesses have the biggest potential of making an actual difference in the world of sustainability today. “The future of sustainability is going to be in businesses, because they tend to be the leaders in trends,” she says. “Following and pushing businesses to be more sustainable is where you’re going to see a lot of movement in sustainability.”

Rheaply is one of these industry leaders that is making real strides in sustainability by illustrating the circular economy can work here in the United States. Since its founding, the start-up has helped companies divert more than 14.5 metric tons of waste through more than 5,000 transactions on its platform. That adds up to $1.6 million in cost savings for their clients.

And they’re not done yet. The company recently raised $8 million in funding to continue to scale their business.

“Almost every organization has this problem,” Sullivan says. “Physical items that are just sitting in storage closets or offices. We help bring visibility to these items so they can potentially be reused. Companies can get value out of their items until the very end of their life cycle.”

As sustainability continues to become more mainstream, hopefully the adoption of circular economic practices, and companies like Rheaply, will too. Rheaply’s CEO Garry Cooper, in a press release about the company’s recent funding, expresses his hope that peer organizations will “consider the stakes: either we develop and take to market additional inventive and practical climate tech solutions today, or future generations unnecessarily shoulder an impossible burden.”

Landrum believes government intervention, like what has been enacted across Europe, is the only way to move forward in a really widespread way in the U.S. “The key to change is legislation,” she says. “The E.U. has put all this in force at a federal level, and as a result, look at how far advanced they are.”

Sullivan hopes companies will realize how easy it actually is to implement circular practices into their businesses and how vital it is, and will continue to be, to have sustainability goals.

For now, companies like Rheaply, and Loyolans, like Sullivan and Patel, are leading the way. This type of work “is a really great place to be,” Patel says. “And this is just the beginning.”

Read more stories from the School of Environmental Sustainability.